ڤەکۆلینا بەڕێوەچوونی کۆنفرانسی -

In silico molecular docking and dynamic simulation of eugenol compounds against breast cancer

ڤەکۆلینا بەڕێوەچوونی کۆنفرانسی -

In silico molecular docking and dynamic simulation of eugenol compounds against breast cancer

...

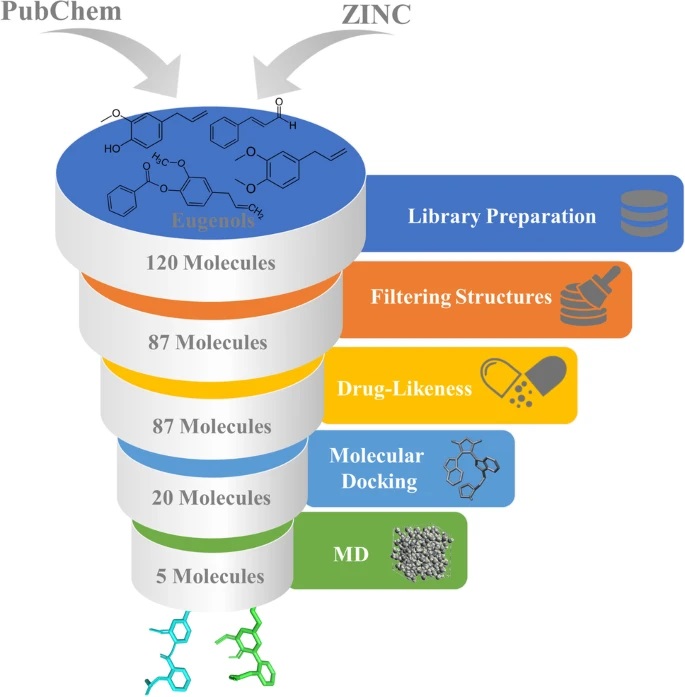

Breast cancer is one of the most severe problems, and it is the primary cause of cancer-related death in females worldwide. The adverse effects and therapeutic resistance development are among the most potent clinical issues for potent medications for breast cancer treatment. The eugenol molecules have a significant affinity for breast cancer receptors. The aim of the study has been on the eugenol compounds, which has potent actions on Erα, PR, EGFR, CDK2, mTOR, ERBB2, c-Src, HSP90, and chemokines receptors inhibition. Initially, the drug-likeness property was examined to evaluate the anti-breast cancer activity by applying Lipinski’s rule of five on 120 eugenol molecules. Further, structure-based virtual screening was performed via molecular docking, as protein-like interactions play a vital role in drug development. The 3D structure of the receptors has been acquired from the protein data bank and is docked with 87 3D PubChem and ZINC structures of eugenol compounds, and five FDA-approved anti-cancer drugs using AutoDock Vina. Then, the compounds were subjected to three replica molecular dynamic simulations run of 100 ns per system. The results were evaluated using root mean square deviation (RMSD), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), and protein–ligand interactions to indicate protein–ligand complex stability. The results confirm that Eugenol cinnamaldehyde has the best docking score for breast cancer, followed by Aspirin eugenol ester and 4-Allyl-2-methoxyphenyl cinnamate. From the results obtained from in silico studies, we propose that the selected eugenols can be further investigated and evaluated for further lead optimization and drug development.

Citation Information

- Lokhande KB, Nagar S, Swamy KV (2019) Molecular interaction studies of Deguelin and its derivatives with Cyclin D1 and Cyclin E in cancer cell signaling pathway: the computational approach. Sci Rep 9:1–13

- Article

- CAS

- Google Scholar

- Rampun A, Morrow PJ, Scotney BW, Wang H (2020) Breast density classification in mammograms: an investigation of encoding techniques in binary-based local patterns. Comput Biol Med 122:103842

- Article

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- Akram M, Iqbal M, Daniyal M, Khan AU (2017) Awareness and current knowledge of breast cancer. Biol Res 50:1–23

- Article

- CAS

- Google Scholar

- Kuhl H, Schneider HPG (2013) Progesterone–promoter or inhibitor of breast cancer. Climacteric 16:54–68

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- Saha Roy S, Vadlamudi RK (2012) Role of estrogen receptor signaling in breast cancer metastasis. Int J Breast Cancer 2012

- Thomas C, Gustafsson J-Å (2011) The different roles of ER subtypes in cancer biology and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 11:597–608

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- Hayashi SI, Eguchi H, Tanimoto K et al (2003) The expression and function of estrogen receptor alpha and beta in human breast cancer and its clinical application. Endocr Relat Cancer 10:193–202

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- Salih AK, Fentiman IS (2001) Breast cancer prevention: present and future. Cancer Treat Rev 27:261–273

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- Wang Z-Y, Yin L (2015) Estrogen receptor alpha-36 (ER-α36): a new player in human breast cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol 418:193–206

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- Acharya R, Chacko S, Bose P et al (2019) Structure based multitargeted molecular docking analysis of selected furanocoumarins against breast cancer. Sci Rep 9:1–13

- Article

- Google Scholar

- Kiani J, Khan A, Khawar H et al (2006) Estrogen receptor α-negative and progesterone receptor-positive breast cancer: Lab error or real entity? Pathol Oncol Res 12:223–227

- Article

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- Costa R, Shah AN, Santa-Maria CA et al (2017) Targeting epidermal growth factor receptor in triple negative breast cancer: new discoveries and practical insights for drug development. Cancer Treat Rev 53:111–119

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- Palma G, Frasci G, Chirico A et al (2015) Triple negative breast cancer: looking for the missing link between biology and treatments. Oncotarget 6:26560

- Article

- PubMed

- PubMed Central

- Google Scholar

- Reddy PS, Lokhande KB, Nagar S et al (2018) Molecular modeling, docking, dynamics and simulation of gefitinib and its derivatives with EGFR in non-small cell lung cancer. Curr Comput Aided Drug Des 14:246–252

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- Ding L, Cao J, Lin W et al (2020) The roles of cyclin-dependent kinases in cell-cycle progression and therapeutic strategies in human breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci 21:1960

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed Central

- Google Scholar

- Carraway H, Hidalgo M (2004) New targets for therapy in breast cancer: mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) antagonists. Breast Cancer Res 6:1–6

- Article

- CAS

- Google Scholar

- Gee JMW, Robertson JFR, Ellis IO, Nicholson RI (2001) Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase is associated with poor response to anti-hormonal therapy and decreased patient survival in clinical breast cancer. Int J cancer 95:247–254

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- Ferrando IM, Chaerkady R, Zhong J et al (2012) Identification of targets of c-Src tyrosine kinase by chemical complementation and phosphoproteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics 11:355–369

- Article

- PubMed

- PubMed Central

- CAS

- Google Scholar

- Zagouri F, Bournakis E, Koutsoukos K, Papadimitriou CA (2012) Heat shock protein 90 (hsp90) expression and breast cancer. Pharmaceuticals 5:1008–1020

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- PubMed Central

- Google Scholar

- Liu H, Yang Z, Lu W et al (2020) Chemokines and chemokine receptors: a new strategy for breast cancer therapy. Cancer Med 9:3786–3799

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- PubMed Central

- Google Scholar

- Vela M, Aris M, Llorente M et al (2015) Chemokine receptor-specific antibodies in cancer immunotherapy: achievements and challenges. Front Immunol 6:12

- Article

- PubMed

- PubMed Central

- CAS

- Google Scholar

- Al-Sharif I, Remmal A, Aboussekhra A (2013) Eugenol triggers apoptosis in breast cancer cells through E2F1/survivin down-regulation. BMC Cancer 13:1–10

- Article

- Google Scholar

- Abdullah ML, Hafez MM, Al-Hoshani A, Al-Shabanah O (2018) Anti-metastatic and anti-proliferative activity of eugenol against triple negative and HER2 positive breast cancer cells. BMC Complement Altern Med 18:1–11

- Article

- CAS

- Google Scholar

- Islam SS, Al-Sharif I, Sultan A et al (2018) Eugenol potentiates cisplatin anti-cancer activity through inhibition of ALDH-positive breast cancer stem cells and the NF-κB signaling pathway. Mol Carcinog 57:333–346

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- Bezerra DP, Militão GCG, De Morais MC, De Sousa DP (2017) The dual antioxidant/prooxidant effect of eugenol and its action in cancer development and treatment. Nutrients 9:1367

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed Central

- Google Scholar

- Ma M, Ma Y, Zhang G-J et al (2017) Eugenol alleviated breast precancerous lesions through HER2/PI3K-AKT pathway-induced cell apoptosis and S-phase arrest. Oncotarget 8:56296

- Article

- PubMed

- PubMed Central

- Google Scholar

- Yan X, Zhang G, Bie F et al (2017) Eugenol inhibits oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid oxidation via downregulation of c-Myc/PGC-1β/ERRα signaling pathway in MCF10A-ras cells. Sci Rep 7:1–13

- Article

- CAS

- Google Scholar

- Fangjun L, Zhijia Y (2018) Tumor suppressive roles of eugenol in human lung cancer cells. Thorac Cancer 9:25–29

- Article

- PubMed

- CAS

- Google Scholar

- Hussain A, Brahmbhatt K, Priyani A et al (2011) Eugenol enhances the chemotherapeutic potential of gemcitabine and induces anticarcinogenic and anti-inflammatory activity in human cervical cancer cells. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 26:519–527

- CAS

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- Carrasco AH, Espinoza CL, Cardile V et al (2008) Eugenol and its synthetic analogues inhibit cell growth of human cancer cells (Part I). J Braz Chem Soc 19:543–548

- Article

- Google Scholar

- Choudhury P, Barua A, Roy A et al (2021) Eugenol emerges as an elixir by targeting β-catenin, the central cancer stem cell regulator in lung carcinogenesis: an in vivo and in vitro rationale. Food Funct 12:1063–1078

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z et al (2000) The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res 28:235–242

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- PubMed Central

- Google Scholar

- 2IOK, Dykstra KD, Guo L, Birzin ET et al (2007) Estrogen receptor ligands. Part 16: 2-Aryl indoles as highly subtype selective ligands for ERα. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 17:2322–2328

- Article

- CAS

- Google Scholar

- 4OAR, Petit-Topin I, Fay M, Resche-Rigon M et al (2014) Molecular determinants of the recognition of ulipristal acetate by oxo-steroid receptors. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 144:427–435

- Article

- CAS

- Google Scholar

- 2J6M, Yun C-H, Boggon TJ, Li Y et al (2007) Structures of lung cancer-derived EGFR mutants and inhibitor complexes: mechanism of activation and insights into differential inhibitor sensitivity. Cancer Cell 11:217–227

- Article

- CAS

- Google Scholar

- 4RJ3, Hanan EJ, Eigenbrot C, Bryan MC et al (2014) Discovery of selective and noncovalent diaminopyrimidine-based inhibitors of epidermal growth factor receptor containing the T790M resistance mutation. J Med Chem 57:10176–10191

- Article

- CAS

- Google Scholar

- 4DRH: März AM, Fabian A-K, Kozany C et al (2013) Large FK506-binding proteins shape the pharmacology of rapamycin. Mol Cell Biol 33:1357–1367

- 2A9I: Lasker M V, Gajjar MM, Nair SK (2005) Cutting edge: molecular structure of the IL-1R-associated kinase-4 death domain and its implications for TLR signaling. J Immunol 175:4175–4179

- 2SRC: Xu W, Doshi A, Lei M et al (1999) Crystal structures of c-Src reveal features of its autoinhibitory mechanism. Mol Cell 3:629–638

- 2VCJ: Brough PA, Aherne W, Barril X et al (2008) 4, 5-diarylisoxazole Hsp90 chaperone inhibitors: potential therapeutic agents for the treatment of cancer. J Med Chem 51:196–218

- 4JL7: Lu G, Wu Y, Jiang Y et al (2013) Structural insights into neutrophilic migration revealed by the crystal structure of the chemokine receptor CXCR2 in complex with the first PDZ domain of NHERF1. PLoS One 8:e76219

- 3OE6: Wu B, Chien EYT, Mol CD, et al (2010) Structures of the CXCR4 chemokine GPCR with small-molecule and cyclic peptide antagonists. Science (80- ) 330:1066–1071

- 4MBS: Tan Q, Zhu Y, Li J, et al (2013) Structure of the CCR5 chemokine receptor–HIV entry inhibitor maraviroc complex. Science (80- ) 341:1387–1390

- Trott O, Olson AJ (2010) AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem 31:455–461

- CAS

- PubMed

- PubMed Central

- Google Scholar

- Kim S, Chen J, Cheng T et al (2021) PubChem in 2021: new data content and improved web interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res 49:D1388–D1395

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- Sterling T, Irwin JJ (2015) ZINC 15–ligand discovery for everyone. J Chem Inf Model 55:2324–2337

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- PubMed Central

- Google Scholar

- O’Boyle NM, Banck M, James CA et al (2011) Open Babel: an open chemical toolbox. J Cheminform 3:1–14

- CAS

- Google Scholar

- Wishart DS, Feunang YD, Guo AC et al (2018) DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res 46:D1074–D1082

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- Molinspiration Cheminformatics. In: Nov. ulica. https://www.molinspiration.com/

- Lipinski CA (2000) Drug-like properties and the causes of poor solubility and poor permeability. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 44:235–249

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- Chagas CM, Moss S, Alisaraie L (2018) Drug metabolites and their effects on the development of adverse reactions: revisiting Lipinski’s Rule of Five. Int J Pharm 549:133–149

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- Google Scholar

- Release S (2017) 3: Desmond molecular dynamics system, DE Shaw research, New York, NY, 2017. Maest Interoperability Tools, Schrödinger, New York, NY

- Pushpalatha R, Selvamuthukumar S, Kilimozhi D (2017) Comparative insilico docking analysis of curcumin and resveratrol on breast cancer proteins and their synergistic effect on MCF-7 cell line. J Young Pharm 9:480

- Article

- CAS

- Google Scholar

- DeBono A, Thomas DR, Lundberg L et al (2019) Novel RU486 (mifepristone) analogues with increased activity against Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis Virus but reduced progesterone receptor antagonistic activity. Sci Rep 9:1–19

- Article

- CAS

- Google Scholar

- Barzegar M, Ma S, Zhang C et al (2017) SKLB188 inhibits the growth of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma by suppressing EGFR signalling. Br J Cancer 117:1154–1163

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- PubMed Central

- Google Scholar

- Liu Z, Wang F, Zhou Z-W et al (2017) Alisertib induces G2/M arrest, apoptosis, and autophagy via PI3K/Akt/mTOR-and p38 MAPK-mediated pathways in human glioblastoma cells. Am J Transl Res 9:845

- CAS

- PubMed

- PubMed Central

- Google Scholar

- Ding Y, Fang Y, Moreno J et al (2016) Assessing the similarity of ligand binding conformations with the Contact Mode Score. Comput Biol Chem 64:403–413

- Article

- CAS

- PubMed

- PubMed Central

- Google Scholar

- García-Godoy MJ, López-Camacho E, García-Nieto J et al (2016) Molecular docking optimization in the context of multi-drug resistant and sensitive EGFR mutants. Molecules 21:1575